Ewa Chrusciel is a poet and translator working in English and Polish. Her poems have appeared in many books and magazines in Poland, England, Italy, and the United States, including Jubilat, Boston Review, Colorado Review, Lana Turner, Spoon River Review, and Aufgabe. She’s translated Jack London, Joseph Conrad, and I.B. Singer as well as some contemporary American poets into Polish. She is an associate professor of humanities at Colby-Sawyer College. Her website is http://www.echrusciel.net/.

Ewa recently sat down with Shanta Lee to talk about poetry, opening up language, and how cognitive linguistics influenced her work. Ewa’s latest publication is Yours, Purple Gallinule, published by Omnidawn.

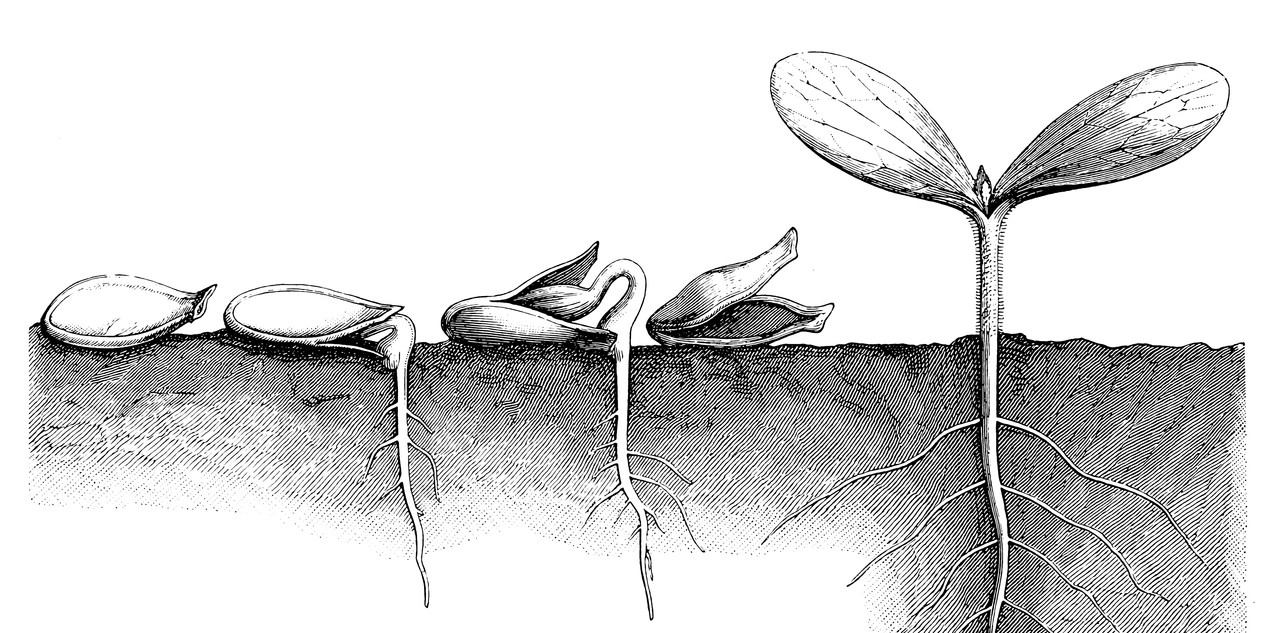

Shanta Lee: What is the radicle of your work? Your first roots that remain from your first book to the most recent book that you can pinpoint?

Ewa Chrusciel: That’s interesting because I think the radicle was my switch from writing in Polish to writing in English. When I came over to the U.S., I was already thirty and I was, I think, specifically to do my Ph.D. And I had my first book. Within my first or second year of my Ph.D., I had my first book in Polish published. These were very short, epigrammatic poems, and my friends in the Ph.D. program wanted me to translate some of the poems so they could understand what my book was about. I translated some of the poems, but I also got bored doing it and I gave myself a lot of poetic license. I started to sort of write new poems and mistranslate them. That work actually encouraged me to take one creative writing workshop within the Ph.D. program – I studied English in my program, I do not have an MFA – at Illinois State University. And that’s why I was reading [poet, essayist, and translator] Lyn Hejinian. That was also a radical switch for me, because in Poland, I was more fond, attached to masters of Polish poetry who were quite canonical. While most of it was free verse, they often referred to sort of very dignified writing and higher tastes, and the poems that were in the European sort of poetics at the time. Being introduced to this new work gave me courage to break out of the constraints of my own, native language. I’d written this polemic for this creative writing class, but because the reception was so generous, the feedback I got along with sending it around – it got published in various magazines – gave me total encouragement to keep going.

A lot of my first book was about growing up in communist Poland during the Iron Curtain days, exploring the function of memory, childhood, and homesickness. So actually, speaking of roots and germination, the title of the book is interesting. It’s called Strata, which in Polish means “a loss,” but in English it means layers, geological layers, you know, it’s multifaceted. In a sense, changing my politics completely, radically having that title. On the one hand, it’s like an unhealable rift between you and your country, and you are leaving your language behind because little did I know, I thought I would keep both intact, but the truth is English kind of took over because I live here. So the truth is, I was also dealing with this sort of unconscious grief, but I already knew that by realizing if I stay, I am leaving my language behind so that grief was kind of unconscious, but it was already happening. There was an unhealed, but healable, rift and sadness about this homesickness at the same time. With it I was discovering new ways of writing, and liberating myself from constraints of my own language.

Shanta Lee: The last time we talked, I loved your answer to one of my questions when you talked about trying to be in a constant state of bewilderment, but also it is like walking within an in-between space. Especially as you just talked about leaving language behind and taking on another language, between the space of cultures. If you had to give someone one ingredient for entering into that state of purposeful in-betweenness or displacement, what would you suggest? What is that ingredient for entering into that state of discovery?

Ewa Chrusciel: Go out of your zone of comfort, or leave the borders that you surround yourself with. And it could be very journey oriented. You could actually fly to another country, pick a country where you do not know the language. And then you see things and you become like a baby, what’s your language? But be brave. Communicate with people, use your gestures. A poem that describes what I am talking about is by Craig Raine, “ A Martian Sends a Postcard Home.” In the poem, a Martian does not understand simple things so he doesn’t know what the clock is and he doesn’t know what the car is. We should practice that kind of needing familiarization. That gets us away from using cliches, gets us away from using the language the way we know, you know? The most visceral would be to travel, but you can also travel by imagining. Linguistically getting out of your comfort zone.

Shanta Lee: As a scholar, one of your areas of study is cognitive poetics∗. What have you seen or experienced as the change with our engagement with poetry? What are the shifts within your own work in terms of thinking about cognitive poetics?

Ewa Chrusciel: It is a great question, a complex one. To me, the cognitive poetics lens helped me immensely. It made me realize how when I read poetry, I look for schemas, I look for constellations. Consciously or unconsciously, we create various trajectories in our work and most of it is unconscious. We do have recurring images, obsessions that haunt us and even if we avoid them, they disguise themselves as something else and come back. Cognitive linguistics made me more aware of this so, for me, Emily Dickinson wasn’t just a plethora of separate texts, I actually saw patterns in her work that made me realize, “Oh, my goodness, these are her most important concepts.” I think it very much helped me to read other poets and realize that we all use metaphors as poets. We often do familiarize, these metaphors that can be cliched or we rework them. The work of poetry is like a deeper plumbing work, a deeper work of digging. We all, in our everyday life, utilize a metaphor of container.

Like right now, I’m in a container metaphor, because I am in a classroom and you are in a classroom, and we are collaborating, right? It’s a container metaphor. And when you fall in love, it’s also a container metaphor, the preposition in, you know? So cognitive poetics helped me to weave in grammar. It helps me with my teaching, too. It helps me in understanding and reading other poets. I’ve been reading Palestinian poet Hala Alyan, and I will be interviewing her. She has amazing themes – interactive fictions, erasure poems, and she has more traditional poems. Like look at this. [Ewa takes a moment to show me the book and how some of the poems are formatted on the page before continuing.] So, my initial training in cognitive linguistics – which was based on consciously perceiving metaphor, understanding metaphor, and how metaphor can be also carried out simply by preposition, because metaphor is not just what we think as metaphor, but it could be a trajectory and movement – helps me to read. Alyan does this in her work because it is actually talking about exile, she’s talking also about specific places and people, she’s interweaving all those things.

Shanta Lee: This question about cognitive poetics also gets into something I read in an interview where you were talking about open versus closed texts. Within your thesis, you land at the idea of texts being open and closed. As a writer, what kind of text do you seek to produce? Is it open? Is it closed? Is it between?

Ewa Chrusciel: It fascinated me profoundly when I was doing my Ph.D. because I also saw that binary that people either call closed or open, and even my life, that was fascinating to me. And my life is such an open text. She [Lyn Hejinian in The Language of Inquiry] talks about metonymy† as being this instrument of openness, because it is more ambiguous than the metaphor, which is more forced. Her text is so open and yet, as a reader, we of course close many gaps, you know, because that’s how our mind works. We want to find patterns. We want to unpack the crossword, unpack the mystery when we read the poem. We look for some kind of solutions, answers, and we know it’s multifaceted, but I think our brain always wants some type of closure. I think it’s always an assimilation between how do you have a bit of closure, but also leave the door ajar? Like in jazz, jazz is such a beautiful improvisation, but it repeats certain themes so it makes it cohere. And the door is always ajar. And that’s what fascinates me in poems the most. Now in my poetry, I have to say it’s hard work! Sometimes I achieve it, sometimes I don’t. I love those poems where it almost lingers at the end and is not tied with a bow.

Shanta Lee: As an educator, what do you try to impart upon your students regarding their development as future literarians, poets, and translators? And as humans in general?

Ewa Chrusciel: I get a kick out of seeing the spark of insight in my students’ eyes or the piqued curiosity driven by a new source of knowledge.

In his essay, “Learning to Live,” Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk, educator, and writer, claims that the mission of education is to find your true identity, your innermost self and to understand what authentic freedom means. In other words, the main function of university is to activate “that inmost center, that scintilla animae, that ‘apex’ or ‘spark’ which is a freedom beyond freedom.” Therefore, we should not confuse means with ends or solely focus on the success. Instead, we should ignite our passion, re-discover wonder in the Aristotelian sense.

I like to remind my students that learning begins in wonder. Wonder is demanding. It comes at a cost. It can be disorienting; it can be wounding. Perhaps, the term “bewilderment” even better conveys the discomfort of the process of learning. Fanny Howe defines “bewilderment” as a loss of one’s sense of where one is. As Howe writes, “Bewilderment is an enchantment that follows a complete collapse of reference and reconcilability. It cracks open the dialectic and sees myriads all at once.” It is resolving the irresolvable. Howe quotes a Muslim prayer: “Lord, increase my bewilderment.” In other words, wonder does not always bring comfort. It can cause puzzlement and disorientation. A true learning experience lingers in us. It may confuse us at first. As Dr. Neel Burton notices, the Greek word thauma (miracle) is a linguistic cousin of trauma. Learning comes at the cost of being disturbed.

Shanta Lee: What advice do you have for writers seeking to pay attention to their radicles or original roots of their work as they appear in their creative lives?

Ewa Chrusciel: Not to be afraid to be wounded by beauty. To risk wonder and bewilderment. To let go of their control and let their writing meander, twist, storm the walls of mystery and take them somewhere they have not expected to go. I think that’s the hardest thing for any writer to do.

∗ a school of literary criticism that applies the principles of cognitive science, particularly cognitive psychology, to the interpretation of literary texts.

† figure of speech in which the name of an object or concept is replaced with a word closely related to or suggested by the original.

Read Ewa Chrusciel’s previously published poetry at Big Other