Poet Abbie Kiefer recently sat down with our Radicle Poetry Interviewer, Shanta Lee, to talk about pop culture, loss, navigating the realities of rejection, and what inspires her work. Abbie’s debut full-length collection, Certain Shelter, was recently published by June Road Press.

Shanta Lee: Tell me about your first memory of knowing that poetry was it for you?

Abbie Kiefer: In one of my high school English classes, we read the Linda Pastan poem, “To a Daughter Leaving Home.” The daughter leaving home is only mentioned in the title; the rest of the poem is all about teaching the daughter to ride a bike, and it ends with the speaker saying that her hair was flapping behind her as she’s peddling away—she compares it to a handkerchief waving goodbye. I remember reading this very brief poem and thinking that you could do so much in such a small space. And I wanted to try to do that, too. It felt like an interesting challenge.

Shanta: You are one of the Editors at The Adroit Journal. What catches your eye in terms of the poetry you review and accept?

Abbie: Like anyone, I have my biases and things that appeal to me—pop culture, for example. I really like poems that can take what we might think of as “low-brow” art and address it in a smart, fresh way. I also love a strong storytelling voice. While I think narrative poetry has kind of gone out of fashion, I’m always interested in what a writer can do with narrative.

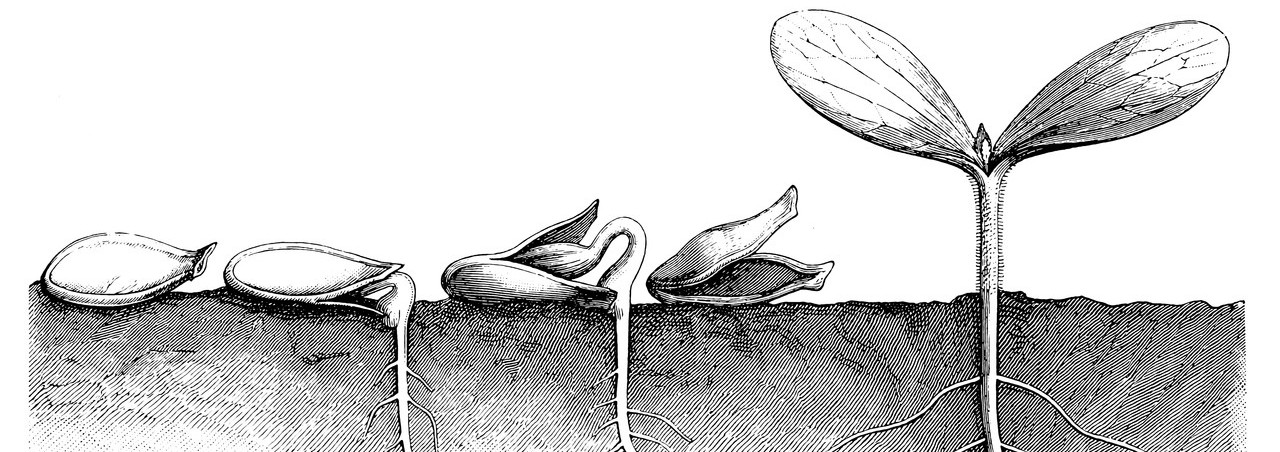

Shanta: Certain Shelter is your debut book. Where would you say the radicle, or the root, of your writing career began?

Abbie: My first paid writing job was in my early 20s as the editor of a weekly community newspaper. This kind of journalism is dying out, which makes me sad, because there’s nothing like a local weekly paper—journalism that’s really rooted in a community.

Since we only came out once a week and were a very small staff—there was me and sometimes a part-time writer, some office support staff, and sometimes a few freelancers—we paid attention to the stories that were most important to the community. We kept an eye on town government, the school board, local crime reporting, all those things. But we really focused on small, personal stories—the kinds of stories that were probably never going to merit coverage in the daily paper.

I will say that I was young and still figuring things out, so sometimes, I was a little cynical about what people thought of as newsworthy. At the same time, I saw so much of what was important to people, what helped them feel connected to their communities, and what made their lives feel meaningful. Just because these stories were small did not mean they weren’t worthy of notice.

I’ve been gone from that job a long time now, but I still think about that work, the people I met there, and the things that were important to them. It’s that kind of noticing that informs how I work as a poet. It also might be why I like to write about subject matter that might feel mundane. I love writing about the quotidian because I saw how much of our lives are given to that.

Shanta: It’s funny, I sometimes ingest the low-brow as much as the high-brow. Sometimes, while washing dishes, I will listen to random stories being told by strangers I will never meet, so there is a charm in the quotidian, for sure. I am curious about the moment you knew that this book was shaping into a collection. Did you begin with the collection in mind, or was it something you bumped into?

Abbie: Certain Shelter took a long time. When I started writing this book, I had been on a long writing break—almost four years. It was the longest break I’d taken since I’d become serious about writing. My mom died, and it took a while before I felt like writing anything. When I started to get back into it, I told myself, “Just write some poems. Just make something creative.”

So, I let myself ease back in. The idea of an entire poetry collection felt overwhelming. But I am also super Type A, and I like having a plan with a goal. Once I started creating some of the poems, I realized there was a thread, and I wanted to organize them. What initially came to mind was a chapbook, which felt manageable. After I pulled the work into what I thought would be a chapbook manuscript, someone I really respected read it and said she saw the work moving beyond elegy and going in other directions. She was telling me that there was more to explore.

This feedback appealed to me as an assignment: a sense of permission and direction for the work. The point at which the book came together for me as a collection was when I realized there were two things I was writing about: the loss of the speaker’s mother and the speaker’s complicated feelings about being from a hometown that was in economic decline. I realized that I was not just writing about loss because of death, but also a loss of home, loss of comfort, and the loss of belonging. I’m not sure I would have ever come to this awareness if someone hadn’t said to me, “I think you need to try some different directions.”

Shanta: Let’s talk about the back-end of bringing this into the world, because that is certainly a part of the work. You mentioned that your manuscript was rejected more than 50 times as it was coming into the world. How did you navigate the rejection? Did it shift or impact the way you reviewed poetry as a poetry editor?

Abbie: At first, I did not navigate it well. I’d worked on the book for about five years, and I felt like I’d invested so much in it. Everyone feels like this, right? Everyone invests in their work, and it feels personal to everyone. It’s vulnerable. So it’s hard not to look at the rejections and ask yourself, “Is there something fundamentally flawed here, in my work, that I’m not seeing?”

When navigating rejections, a couple of things happen. I think you get enough rejections that you become less sensitive to them. You realize that it is not just happening to you—you are one of 957 people who got rejected from that book contest because 958 writers all sent in very good manuscripts. Also, the more reading I was doing for Adroit—before becoming an editor, I read for Adroit for years—the more I understood that publishers do really receive huge amounts of excellent work. You know when you get those rejections that say, “We had so much very good, very publishable work”? I used to see this as their way of trying to make me feel better, but it is absolutely true. As a reader and now, as an editor, I realize that journals get far more excellent work than they could ever publish. Knowing that makes rejection feel less personal.

Shanta: I like how being involved in the process also helped you navigate this process in your work. What is your advice for others who are starting to put their work into the world, who may not have published their first book yet?

Abbie: The first thing I would say is to get a good writing buddy who’s going to read your stuff and appreciate it. That is one thing that’s made a huge difference for me. I have a poet friend who regularly swaps poems with me. We appreciate each other’s work, and we can articulate what about the work we appreciate. And to me, that carries me through so many rejections because I know someone is reading it, getting it, and caring about it. If you are out there and ready to start submitting a book, or even just poems, you are going to get rejections. That’s just the nature of it. Having a friend walk through that with you will make it more tolerable.

Another thing about this process is that it requires patience. It took me several years to find the right publisher for this book. I am not alone in that experience. I have heard of people going five or seven years of waiting, but they believe in the work, so they are willing to keep sending it out.

Shanta: Your collection is clearly based in place, specifically, Maine, but there are also threads about the passage of time or time markers within your work as it relates to pop culture, including M*A*S*H, Cheers, and Bewitched, to name a few. What has your attention in this current moment, especially within pop culture, that might be inspiring your pen?

Abbie: I’ve been watching a lot of Top Chef. I open the streaming service, and there are 27 seasons available, and I’m like, “Hallelujah! I’m going to watch all of these seasons!” I appreciate that the show is intense, but not in a way that is going to alter history. I can appreciate the intensity of it and the fact that these people care so deeply about something so specific. I like seeing how invested these chefs get in what they are doing. It makes me feel like I’m not so weird for also having that intensity about my work. It makes me think, “Okay, I’m not alone.”

Shanta: How do you envision other directions for your work? What are you working on now? What would you like to explore that you haven’t yet?

Abbie: I’m always thinking, “What’s the next thing?” I like to have a project going. So, what’s churning around my brain right now is shopping malls. I feel like malls are really tied to a specific era, the era when I was in adolescence. I’m fascinated by people gathering at shopping malls. Now that malls have fallen out of favor, what’s happening to the buildings? It’s still early, and I am still doing a lot of research and reading. We’ll see where it goes!

You can read more of Abbie’s work here.