The morning Nadine’s feathers sprouted, a light snow fell. She was standing outside, watching Meg board the school bus, noticing how the little girl’s hair, frizzy like her own, glistened with snow, making Meg—or Meg’s hair—look surprised, an electrified Who, me? Like a shocked halo. Or a crown, afloat.

The bus eased down the street, and as Nadine waved, the back of her hand prickled.

For some reason, she thought about her dad. Nadine wasn’t the least bit like him—lucky for Meg. When Nadine was a child and would daydream, Dad would rap her on her frizzy head and bark, “Anybody home?” Oh, her sore head. She wished she could have hit him back. She wished she hadn’t loved him.

The memory festered. The prickling under her skin spread. While snow flattened Nadine’s hair, recalled griefs multiplied from this singular ache, like branches from a tree or barbs from a shaft: bad dad, failed college attempt, the accident and miscarriage, the totaled car, the bills, some still unpaid. Too much, too heavy to shake off.

She held up her fist. It wore a fluffy down.

The feathering had reached her wrist by the time Nadine got to work. It had also stiffened and taken on color. Red. She managed the produce section at Save-More, and the development looked like an accessory to her apron, a showgirl’s glove. Nadine had to admit: She liked it.

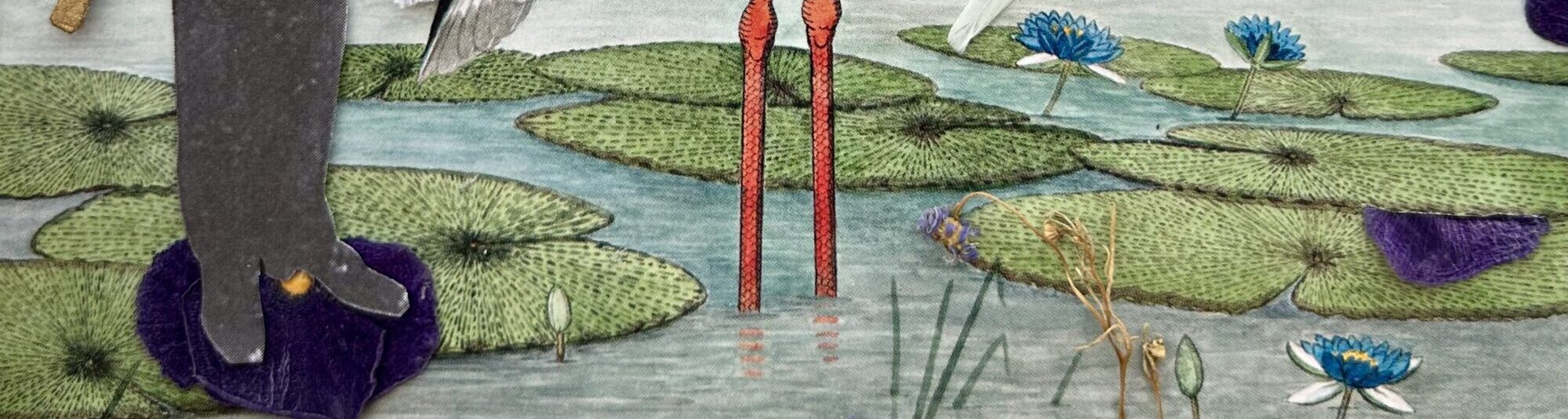

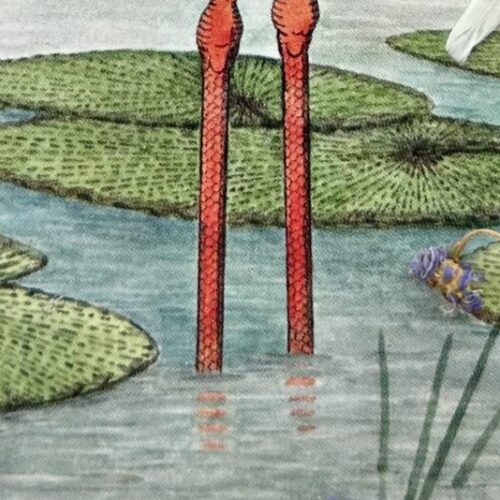

As she restocked the bananas, her feathered hand seemed right at home, a tropical bird preening in a fruitful plant. The sight reminded her of her mother, how on hot days by Lake Erie, Mom wouldn’t swim with Nadine but stand ankle-deep in the water and look for beach glass. Straightening to inspect her find, she’d unfurl a trail of lake from her palm, like a fan. Bony-kneed Mom: a water bird, gentle and flightless.

Nadine returned home. At last, a full wing had formed. It might have been a shawl, unevenly draped along her right shoulder and arm. A matador’s cape. But no. It was a wing.

And Nadine, who wasn’t young, nevertheless felt as a young person does, when the hair dries with more curl than frizz and the right outfit flatters the form. That rush.

Nadine threw out her wing and marveled at the interlocked display, then repeated the motion, swifter this time.

She hugged herself with the wing, tucked in her feathers, and sensed she was safe.

No doubt, Meg would burst into the kitchen, toss aside her backpack, spy the wing, and freak. For certain, Nadine’s husband, Kyle, slogging into the house after a day in a windowless cubicle, would confront the manifestation and sink into despair.

Sure, people would talk. So what? To squawk at the weirdness was to overlook the wonder. She’d show her family:

See how I can enfold and warm you?

See how I can hide us?

And should a second wing sprout, what luck. Then we can always get away.

Melissa Ostrom

Melissa Ostrom is a teacher and ceramicist and the author of The Beloved Wild (Feiwel & Friends, 2018), a Junior Library Guild book and an Amelia Bloomer Award selection, and Unleaving (Feiwel & Friends, 2019). Her stories have appeared in many journals and best-of anthologies. She lives with her husband, children, and dog Mocha in Western New York. Learn more at www.melissaostrom.com or find her on Twitter or Bluesky @melostrom.