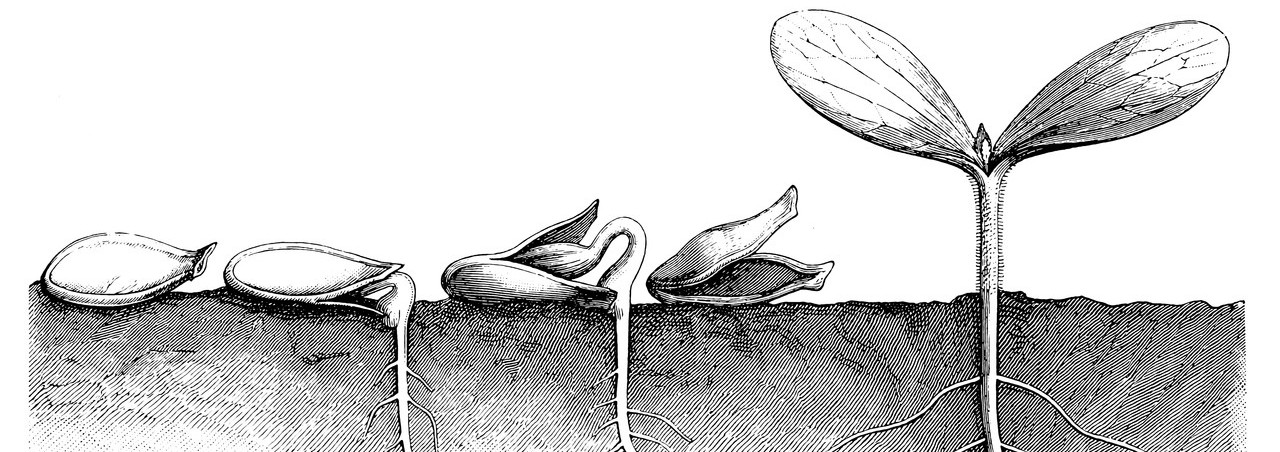

Sue William Silverman is no stranger to the writing life, nor the winding trajectory to publication. Penning poetry, fiction, and personal and craft essays, Silverman also has five memoirs to her name, including her newly released flash-micro essay collection Selected Misdemeanors: Essays at the Mercy of the Reader. Her probing forms sift through the landscape of memory like a seasoned agriculturalist. Scythe in hand, she studies the terroir of both trauma and joy, deciding which rows to sow, which patch to resoil, which tree to graft for a more robust harvest. There are little doors inside her sentences that open to these sweeping fields of the past—always through the lens of experience.

Silverman recently sat down with our Nonfiction Editor, Jocelyn Winn, to talk about how she mines formative life events with metaphor, sensory imagery, and perseverance.

Jocelyn: Changing the stories we repeat to ourselves can redirect our own synapses and, thus, narratives. How did you transition from a Washington, D.C., intern to a fiction writer, poet, essayist, memoirist, and teacher?

Sue: I was raised with the belief that being politically involved is good. And it is good! However, after working on Capitol Hill for a few years, I realized it didn’t nourish my soul. I honestly can’t say how the switch to writing took place—except to say that one day I simply began to write. I don’t mean to sound mystical, but it feels mystical. One day I rolled a piece of paper in a typewriter and started typing a novel. And, back then, it probably was more typing than writing since I had no idea what I was doing. I spent at least ten years writing very bad (unpublished) novels before my therapist suggested I write my own story.

I also began adjuncting before publishing my first book. Initially, it was more to earn money. Most writers I knew taught, so, it just seemed to be part of the writer DNA.

But I learned to love teaching. I stayed with it. And after the publication of my second book, I was able to secure a teaching position with the MFA in Writing program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. I find that teaching and writing nourish each other; therefore, I don’t struggle (too much) finding time to write.

Jocelyn: In what ways did completing that debut memoir, Because I Remember Terror, Father, I Remember You?, shift your personal narrative, your career as a writer, and your way in the world?

Sue: I now have more of a sense of self. Before I began to write creative nonfiction, my personal (internal) narrative was kind of a blank slate. I was emotionally lost. Through writing about the self (my self), I discovered my personal narrative. Which is to say that I finally understood deeper meaning around the various stages of my life. Before then, I was too lost to see my “self.” Now, after writing five books of creative nonfiction, I can embrace that lost girl, adolescent, young woman and see her.

Jocelyn: How do your successive memoir collections Love Sick: One Woman’s Journey Through Sexual Addiction, Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew, How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences, and the just-released Selected Misdemeanors each manage to tell a different, at times nonlinear, facet of the story that started with your debut book?

Sue: We all do contain multitudes, so, as writers of creative nonfiction, it’s incumbent upon us to view our lives thematically, as opposed to chronologically. Viewing your life chronologically implies one life. Viewing your life thematically means you have many artistic lives—many narratives to tell. For example, after writing my first memoir about growing up in my incestuous family, the next logical theme to explore was sex addiction that resulted from this childhood. Love Sick, then, revolves around the 28 days I spent in rehab. These two memoirs had straight-through narratives. After they were published, I began to write what I thought were stand-alone essays, not envisioning a book. After a couple of years writing these essays (and publishing some), I began to see a common theme: They all touched on the narrator’s misguided search for spirituality. Once I realized this, I returned to the already written essays to edit and tweak them a bit to be sure they clearly reflected this theme. Then, as I continued to write essays, I wrote with this theme firmly in mind. The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew was the result.

After that book was published, I again began to write what I thought would be stand-alone essays. Once again, a few years in, I discovered a common theme: the narrator’s fear of death—but not just physical death. Some of the essays reflect smaller forms of “death”—such as spiritual and emotional losses (divorce, addiction, etc.).

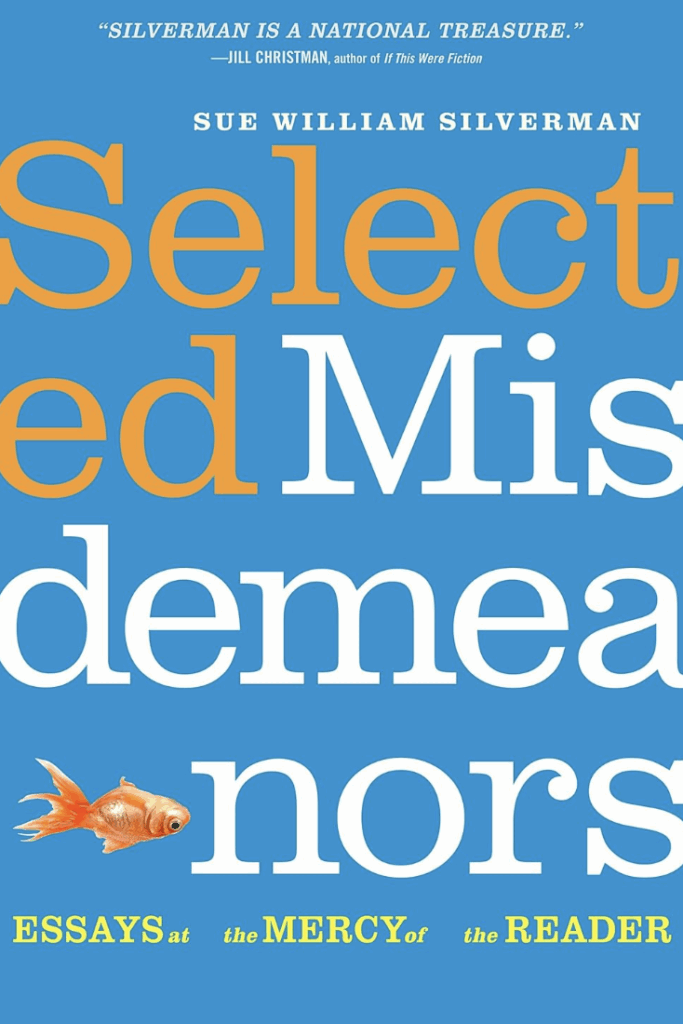

I began to write my new book, Selected Misdemeanors: Essays as the Mercy of the Reader, during the COVID lockdown because I needed something all-encompassing to avoid obsessing too much about the state of the world! And, since I’d written two full-length memoirs and two memoir-in-essays collections, I needed a new challenge: a collection of flash pieces.

Oh, you know, a writer’s tendency is usually to first focus on life’s BIG events: unhappy childhoods, addiction, loss of loved ones, illness. But what about all the time between these big events?! That’s a lot of time—also worth writing about! Essays about snippets of loss, miniature forms of betrayal, small moments of beauty are at the core of Selected Misdemeanors. The overall theme is the narrator’s search for Home (comfort and safety) even as her emotional misdemeanors—such as miscalculations and transgressions involving love—sabotage her attempt to achieve what she thinks she wants.

Jocelyn: Metaphor and sensory imagery are key elements to all your work, levitating those themes to a place of lyricism and simultaneously grounding them in craft. The scarf in Love Sick, for instance, is imbued with a lingering sense of smell to portray loss. The extended metaphor of celestial bodies speaks to fate vs free will in Selected Misdemeanors. Even death becomes personified in How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences. How do you imagine and come to choose short-term and extended metaphors? Do they come to you as if by magic or is it a bit more prescriptive?

Sue: Ah, not magic. The metaphors arise after many years of revision. Frequently, the image is there in an early draft such as that maroon scarf in Love Sick, but, in that instance, I didn’t understand its significance until about four years in.

Another example is the belly-up goldfish on the cover of Selected Misdemeanors. This goldfish, in the essay “Love Deferment,” at first was just a goldfish that died. During the revision process, however, it evolved into a metaphor not just for physical death but for betrayal in matters of love as well as the absence of love. In the essay itself, my unloving boyfriend is away at boot camp; I buy a goldfish for company; I betray my boyfriend by having an affair with his roommate. One of my misdemeanors, then, is the relationship with the roommate. Additionally, when the roommate breaks up with me, I’m so distraught I forget to feed the goldfish. Who dies. Another misdemeanor. But this goldfish is a metaphor within the context of this essay because he encapsulates more than just my misdemeanor of forgetting to feed him. The fish is a metaphor for the loss of love.

Jocelyn: I have to interject here and ask how you come up with your titles. They are themselves poetic devices.

Sue: Thank you! Because I Remember Terror, Father, I Remember You is a line in the book itself. Love Sick is about the 20,462 title that book had before my publisher settled on Love Sick. That was a tough one.

Subsequently, with the essay collections, each had several titles until finally finding the right one. At some point, Selected Misdemeanors was called “Against Ruin.” But that didn’t seem quite right. The whole process is trial and error for the most part! I play around with words a lot, with the meanings I want to evoke, and my partner (also a writer) and I brainstorm.

Jocelyn: In “Mug Shots with Fellow Fugitives” (Selected Misdemeanors), you say about memory, as in photographs, that “each exposure atop another creates a palimpsest.” Indeed, each of your books includes nods to contemporary culture—movies, songs, books, places—that are so ingrained in your memory, they almost stand in for the memory itself. What are some other ways you advise writers to dutifully represent their memories if the details are forgotten?

Sue: Writers of creative nonfiction are after a search for emotional truth—not facts. Memoirs and essays aren’t meant to be academic treatises or legal documents. They are our emotional truths, and, sure, memory can be inexact. But that’s as it should be. How we remember things—and what we remember—is the point! This kind of truth-memory is revelatory of the narrator’s psyche, and we try to portray it metaphorically (“telling it slant”). The metaphorical slanting enhances this emotional truth.

What are the sensory details in your memoir or essay (such as, in my case, that goldfish)? Convey them—describe them in such a way—so they shed light on the narrator’s interiority. Voila! A metaphor.

Jocelyn: In the portrait on the cover of Love Sick and the photo-poems interspersed throughout Selected Misdemeanors, the young women enact visual time stamps for the experienced narrator assessing the beauty and carnage of the younger self. How do you cultivate that vulnerability and ultimate acceptance between the two narrators?

Sue: Full disclosure: The photograph on the cover of Love Sick isn’t me! It’s the actor Sally Pressman who plays me in the movie version of the book. Still, it’s me in the sense that it captures me—I think pretty accurately—at that stage of my life.

The photos in Selected Misdemeanors are, of course, me, and they show me through various stages of my life. They are essays unto themselves, complete with titles and text.

Literary nonfiction doesn’t really exist without the blending of these two voices you mention. The Voice of Innocence is the unaware narrator who can only state what happened at the time of the event in the past. This is an important voice, but, if that’s all we had on the page, it’d be fairly boring, as in “this happened to me, then this happened to me, and then this happened to me.”

Therefore, enter the Voice of Experience, replete with metaphor and reflection, who makes sense of these events that happened in the past. For me, writing this voice is what holds my interest during the writing process. I write to understand what any given event meant/means. I am on a journey of self-discovery. Therefore, I pretty much have to accept this vulnerability: this is who I am.

Jocelyn: Acetylene Torch Songs: Writing True Stories to Ignite the Soul uses your own essaying to exemplify the tenets of craft. Can you speak to the evolution of “creative nonfiction,” a term coined in the late ’90s, and the authorial mask that performs the very unmasking on the page. Your use of flash, speculation, and hybrid forms comes to mind, as does the fairly new concept of memoir in essay.

Sue: This is my personal opinion, but I think the memoir movement, which fully came into its own in the mid-1990s, evolved from the women’s and Civil Right’s movement in the ’60s and ’70s. Women, and those considered “other,” were tired of being silenced. We began with demonstrations, followed by the written word (and other artistic forms), which, in turn, sparked the #MeToo movement.

Yes, it’s true: In the mid-1990s, creative nonfiction mostly focused on rather straightforward memoir. Over time, writers simply realized and embraced the flexibility and fluidity of the form, how it offered space to be experimental and speculative. These experimental forms offer writers other lenses through which to examine our truths. Once the genre of creative nonfiction began to split its seams it simply exploded wide open.

Jocelyn: Your rows of words have been watered well, growing into a hearty body of work that champions all writers and readers. Do you have another memoir in you, or what is your dream project?

Sue: Ah, sorry, a secret. Stay tuned…

You can also read Silverman’s “7-Up as a Cure for Irony” published in Issue 8.2 of The Maine Review.