I heard about Xu before I met him. Ma liked to tell the story when he collapsed in the street while carrying bananas from one side of the town to the other. The vendors made a gurney and rushed him to the hospital. On the way, he woke up and walked back. He could still lift a crate of bananas; that was all he cared about.

Because of this story, I imagined Xu as someone very different from me. I lacked his sense of duty, something Ma had tried to instill in me after we moved to the U.S. when I was a child. She blamed this foreign place for making me naïve and teaching me to abandon familial principles. She often spoke of Xu as the opposite of me—after his father, a drunkard, had lost their family’s house in a game of Mahjong, Xu picked up odd jobs to keep food on the table. The abstract existence of Xu festered like a sore, gnawing at the feeble parts of myself.

After Ma learned of my grandmother’s cancer diagnosis, she suggested that we go back to China together, when in the past, she had gone by herself. “I cannot go back without a son to show for another year,” she said. All I could remember of my grandmother was her smile; the contours of her face and figure were indistinguishable.

That year, I was living at home with Ma to work on my PhD dissertation. During the long summer nights, I heard her muffled crying from my room. I remembered feeling then, how I feel about Xu now—what true loss is, and how it dulls the beating of my heart.

*

At the airport, my uncles and aunts met us with their arms outstretched. I returned their embrace feeling nothing but the air that customarily fills the chasm between strangers. Ma and I got in their car. The heat was unforgiving, and I watched people taking shelter under tarps, selling fruit and fixing cell phones. A group of men were hunched around a table, looking over the spill of cards, blowing cigarette smoke, and eagerly awaiting the next draw.

We drove away from the city center and followed the road where the roots of trees bulged out of the ground and towered above like ancient sculptures. When we arrived at the house, Lao Lao was sitting outside on a stool with her legs stretched out as if bracing for the monsoons. When she smiled, I couldn’t tell she was battling cancer: How was she so filled with life when she was so close to death?

“He’s so much taller than the pictures!” she said as we approached.

More aunts and uncles brought our luggage inside. I tried to conjure the image of the family tree that Ma drew for me on the plane. I smiled and shook their hands.

The house had two rooms and a kitchen. In one room, a light bulb dangled over two beds crammed together. A second had a couch—still in its plastic covering—and an adjacent TV, where the reporter on the screen was talking about the construction of a billion-dollar real estate complex. The kitchen was small for the mouths it had to feed—cabinets with jars of dried huajiao, a small oven with four burnt spirals on top, and a water cooler. The smell of oxtail and winter melon soup clung to my nose.

“Da Ge, we’ve missed you!” A young girl ran over and threw her arms around me. I tensed, surprised that she had called me her brother.

A guy my age, who was leaning against a wall away from the commotion, intervened and carried her off on his shoulder. With the leather strips of her sandals swinging wildly, Mei Li screamed, “Put me down, Xu!”

“Mei Li, don’t bother your brother,” Lao Lao scolded.

She turned her head and asked, “Which brother?”

I then remembered that any older male relative was called Da Ge; maybe this was her effort to become closer to me. I looked at Xu. He was tall and athletic with an angular face and a tight jawline. His pupils were dark obsidian. The sunbaked veneer on his skin and white tank top made him look innocent, untainted by life. Xu stared at me, as if to say: This is my house. I could not muster the words to tell Mei Li that I was not her brother but a visitor. The only power I had was my silence.

*

During the first few days while Ma was dealing with arrangements for Lao Lao’s cancer, Xu and I spent every day together. We were the only ones not old enough to participate in family dealings of money and illness, but not young enough to be oblivious. Initially, I resented our forced companionship together; it was unnatural. I could not tell what Xu was thinking or wanting. At times, I thought he loathed my presence. I already admired his dedication and duty to his family, but now in close proximity, I also envied his build, which was more masculine and definitive than my lanky figure. When I looked at him, I became aware of my thinness.

One day, assuming the role of local tour guide, he took me to a restaurant. We drove down a hill and he pointed to a river, a translucent sliver of turquoise in the mountains.

“This used to be forest,” Xu pointed out the window, “but now it’s all farmland. In ancient times, this area flooded, but our ancestors invented an irrigation system that harnessed the river and nourished the land, making it fertile. We invented irrigation before the Romans, did you know that?” I said I didn’t. It was as if, by the configuration of our upbringings, he wanted to prove himself. I pitied him for this, but grew remorseful: Who am I to judge my own cousin? Unaware of my unease, Xu lit a cigarette and blew the smoke out the window and into the wind.

The restaurant was small and hidden in an alley off the main street. The owner, a middle-aged man with a charcoal-colored goatee and a gentle face, came up to us and embraced Xu as if they were childhood friends. “This is your cousin?” the owner asked. “He looks nothing like you!” After we were seated, the owner immediately placed two steaming bowls of noodles in front of us.

“This is the best lamb hui mian you’ll find in the whole province,” Xu said, smiling. “They make the noodles from scratch every day.” He slurped the noodles and lifted the bowl like a chalice to drink the broth, closing his eyes like a kid with a newfound toy. He took pleasure in eating more than I had expected; perhaps food was his escape. For the first time, I saw that he was someone who could let his guard down. We ate in silence.

After we both finished, I asked him how he knew the owner. He told me that two years ago, he saved the owner’s wife when their house caught on fire from a malfunctioning stove.

“Are you crazy?” I said, raising my voice. “What do their lives matter to you?” I shocked even myself by what I was saying.

“You never know,” he said matter-of-factly, “when your life will depend on someone else.”

*

In the span of a few days, I’d come to think of him more and more as someone who could teach me much about life, and he, too, was curious about what America was like—if it was different from the images on his phone. Neither of us ever had a brother, but we were forming our own sphere, like binary stars coming into orbit. Halfway through the trip, I asked Xu if he could take me on one of his deliveries.

When we arrived, he introduced me to the store owner, and I helped him unload the crates of bananas. The owner, an unkempt man in overalls, went back and reemerged with a roll of one-hundred yuan bills. After Xu counted the money, he said, “This is not what we had agreed to on the phone.”

“You should be grateful that I even trust doing business with you after what your father did.” The store owner spat into the ground as if shooting a dart. “You don’t need my money, just ask your rich American cousin right here!” He started cackling as if he were possessed. Xu clenched his fists behind his back. Once we were back in the car, Xu told me that his father had borrowed forty-thousand yuan from the man and left without a trace; it would take Xu fifteen years to repay it. “Vengeance is a bitch,” he said. He tightened his face, and his fingers trembled on the steering wheel. His whole body was vibrating. I realized then, that this was a daily exercise, that he had grown accustomed to hiding his emotions and enduring life’s forces. But in that moment, beneath his skin festered fear and doubt. I could have broken him with my words.

Toward the end of the trip, I didn’t see Xu much. Ma and I visited various family members in their respective homes, where we were welcomed with fruits, rabbit stew, and baijiu. Sometimes, we went to restaurants where the waiters brought dishes out in rapid succession, placing the dishes in front of us as if it were the final act of a magic trick. During one of these meals, Ma told me there was a family rumor that Xu was dealing drugs. She told me how he dropped out of university and did not attend the remedial classes Ma had paid for; how he moved away from home as a teenager; how he has an illegitimate child in another town. “There’s no way he’s getting all that money from shipping bananas in this middle-of-nowhere town,” she said. The dan dan noodles writhed from her mouth like snakes. “There are limits, even with family.”

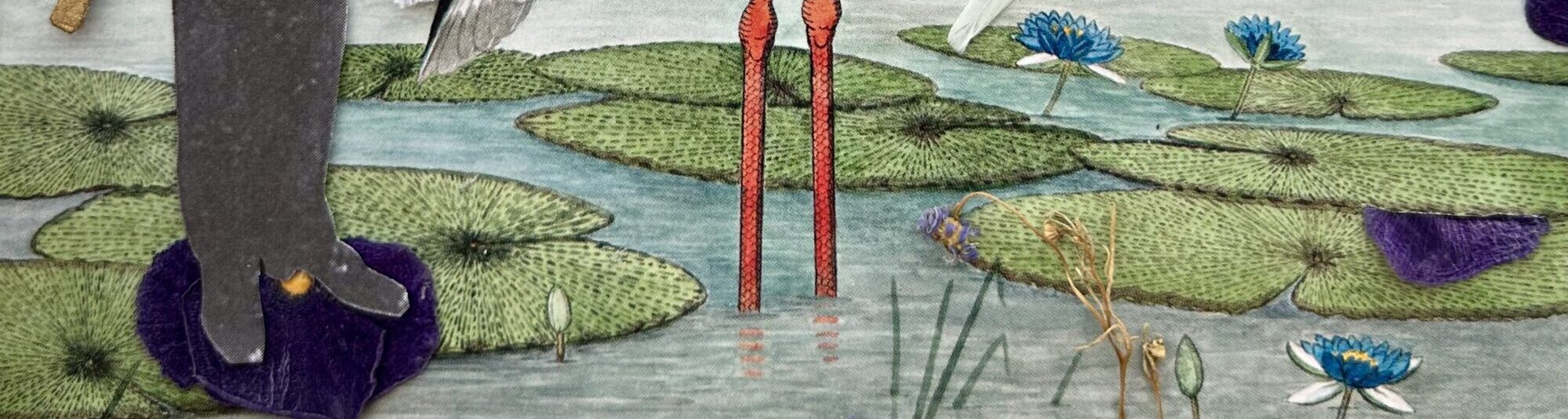

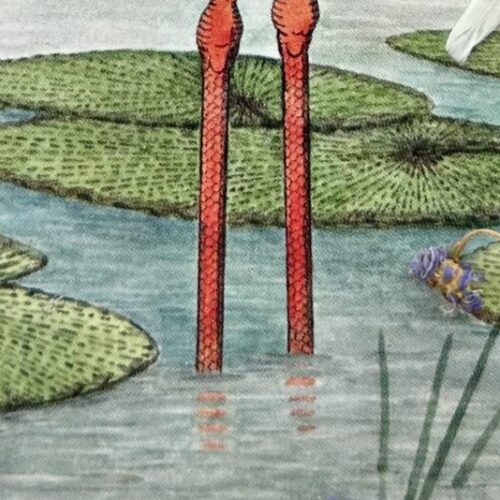

The night before my departure, he showed me the night market, where I was overwhelmed by the charred smoke of spiced lamb meat, the flashing lights from children’s toys, and a crowd so dense, there’s no choice but to breathe on people. Escaping the bustle, we walked to the edge of a lake and stared at the reflection of the moon, its glow under our faces like a dim fire.

“I’ve heard a lot about you from your Ma,” he began, lighting a cigarette. “Stories of success.”

“I’m barely successful,” I laughed, not sure if his idea of “success” could be directly translated from Chinese to English.

“What do you study?” he blew smoke into the air.

“French literature.”

He paused. “Does that make money in America?”

I laughed again and said, “No.”

“I read Le Rouge et le Noir by Stendhal in high school; I liked it,” he said.

I turned my head to look at him, squinting my eyebrows and opening my mouth. Then I closed it. “Why did you like it?”

“It’s about someone who is trapped by his surroundings and wants a better life.”

Xu stared at me with an expressionless face. He told me that in order to make extra money, he made multi-day trips to Vietnam, which had become the largest banana supplier to China. In Vietnam, he met men through online internet cafés, and sometimes these meetings were transactional. He had been diagnosed with HIV, but it didn’t scare him. The doctors told him that it was a chronic disease now, and with the new medications, he would not die early. It took a year for him to absolve the person who gave it to him because this person, like him, didn’t know. He hid his pill bottles in Mei Li’s dolls. He had people he needed to stay alive for.

Around that time, he started coming to this lake. Occasionally, he screamed when no one else was around and saw the fishermen on the boats in the distance turn their heads and then turn their backs. On other days, he stared into the sky and dreamt of a different life where he would not be living in his father’s shadow; he would complete his day’s work, return home, and cook braised carp and stuffed pork buns in peace; he would live close to his family and visit them whenever he decided; he would not have to resort to being intimate with rich, unsavory men; and, more importantly, he would perhaps find love, although he didn’t understand how people became so fragile so quickly.

He spoke to me as if he had known me his whole life, as if I wasn’t a stranger to him and his world. Maybe that’s why.

*

I didn’t see Xu until a year later, when Ma found out that Lao Lao was hospitalized. The chemo didn’t work. My aunts and uncles had known for months, but had waited until it was necessary to let Ma know. Before leaving this time, I made an appointment with Dr. Hernandez, a gay Venezuelan doctor who often shared stories of surviving the AIDS epidemic in the 80s. He was surprised when I told him I wanted to start PrEP since I had declined before. Dr. Hernandez had mentioned that the drugs in PrEP are also used to treat HIV.

Xu and I kept in touch after the first trip, and I was getting the pills for him. He told me that he was dating a Vietnamese guy, Hieu, and they communicated via a translation app. He made more trips to Vietnam, for Hieu and for his job. He told me that they were more accepting there.

The night before our flight, I looked at the bottle of pills on my night stand and imagined giving them to Xu. I didn’t get them out of pity or duty, but out of kindness. I watched the sky shed its sapphire skin, casting streaks of amber into morning. Within the span of a few hours, it was the only color to rule the land.

When we arrived, we went straight to the hospital from the airport. In my grandmother’s hospital room, my aunts and uncles were gathered around her. Ma sat on the edge of her bed, her tears dampening the hospital gown. Lao Lao, who still had a spark in her eyes, lifted her oxygen mask, and beckoned me closer.

“Don’t worry about me. I lived long enough to see you grow up and that’s what matters.”

Xu was in the corner, dressed in a hoodie, long black sweatpants, and flip-flops. We looked at each other for a brief moment. He held me in his eyes as if yearning to tell me something. His back was hunched over, and he didn’t hold his head up, though I could see the dark bags under his eyes, as if he didn’t sleep the night before. He lacked confidence this time, seemingly unable to take on what the world threw at him. I wondered if he had run out of his medications and the disease had worsened, or if he had been threatened by a gang, or if he had been caught with Hieu, or if he had advanced to more dangerous activities for higher profit.

A few days later, Xu took me to the same lake where he had first confided in me. We sat on a bench, looking into the night. The water was still, undisturbed by the wind.

“Are you okay?”

“Hieu and I broke up,” he said.

“Why?”

He didn’t respond. I took this as an opportunity to pull the PrEP bottle out of my pocket and hand it to him.

“I can’t accept this,” he said, looking at the bottle and taking out a cigarette.

“I know you have them here, but you have to get them through the black market, right?”

He nodded. He shuffled in his pants for a lighter. The muscles in his face tensed as if trying to expunge resentment from his body.

“When do you leave tomorrow?”

“Two o’clock.”

“To America?”

“Yes,” which was the only word I could muster. I heard the faint bustle of the market in the background. The sound of water faltering on rock filled the silence between us and held my tongue in place. He leaned in, and before I could notice that his lips were trembling, they touched mine, and my body surrendered to an arresting electricity. My heart turned to steel. My head started to spin as I yanked away, stripping the cord of life that had momentarily sustained us. He was still, in the same spot. Towards the other end of the shore, the night market was closing and the lights flickered out. I looked up and saw the sky folding onto itself, engulfing us in its collapse.

*

Now, years later, I sometimes think about Xu. After the second trip, I have gone back to China several times to visit family, but I have not seen or spoken to Xu since. I sent him messages but he never responded. I heard from my aunts and uncles that he started his own trucking business and moved to Vietnam. I wonder if, at times, he feels alone. I am living in a different country and have grown accustomed to a daily feeling of alienness. The year after the second trip to China, I defended my PhD and worked as an adjunct professor teaching French literature in Boston, then Philadelphia, and eventually Edinburgh, where I met my husband, Ivan. We live near the city center and host dinner parties with charcuterie for our friends who have come from across the world to study or work in this historic city. On weekends, Ivan and I go out to our cottage by the sea. I spend hours looking out onto the water. Further ahead, where the River Forth and the North Sea meet, the waves bristle with glistening scales moving with the sun.

Today, I walk the length of the stone pier and watch a fishing boat far from shore rocking back and forth in the swells. I wonder how small boats like that can sail so far from shore, and who would rescue them if they tipped.

Lanbo Yang

Lanbo Yang is a writer and resident physician in obstetrics and gynecology at Tulane University in New Orleans, LA. He was born in Beijing, China, grew up in Boston, MA, and has studied at Vassar College and Brown University. "Cousins" is his first literary publication.